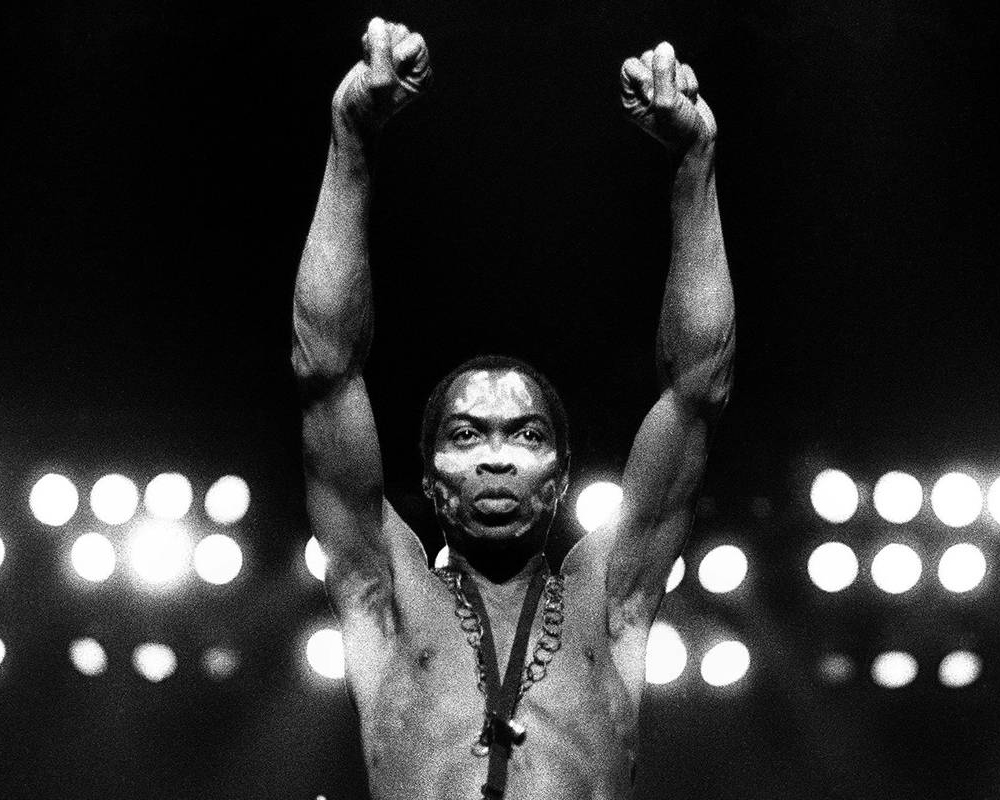

Fela Anikulapo Kuti (1938-1997)

Nigerian musical icon, social critic and political activist

Set forth at dawn

Born on October 15 1938, in Abeokuta western Nigeria, shortly before the start of World War 2, Olufela Ransome-Kuti (now popularly known by his abridged first name, Fela), the third of four children, was a descendant of one of Nigeria’s foremost activist family. His parents, Reverend Israel Ransome-Kuti and Mrs. Olufunmilayo Ransome-Kuti had strong passion for music and politics, providing a remarkable foundational influence. His father who died when Fela was in his teenage years, was a famous educationist, Anglican minster and talented pianist, while his mother was an internationally renowned feminist and women’s right activist, the first woman to drive a car in Nigeria, and a prominent figure in the Nigerian anti-colonial struggles.

After completing his secondary education at the Abeokuta Grammar School, in 1958, when he was just 20 years old, Fela travelled to London, initially intending to study Medicine like his brothers, but subsequently switching path against his mother’s wishes, to Music at the Trinity College of Music from where he graduated in December 1962. In 1961, he married his first wife, Remi Taylor, who he met in London two years earlier. Their first daughter, Omoyeni Kuti, was born in the same year of their marriage, and their first son, Olufemi Kuti, the year after.

Fela’s musical talent and interests were already evident prior to his musical training in London. In his early years in Nigeria, he led a school choir and played piano and percussion. While studying in London, he played trumpet and keyboards in jazz and funk bands. In 1959, in his first year at the Trinity College, Fela formed his first musical group, ‘Fela Ransome-Kuti and his Highlife Rakers’, which he would dissolve a year later to create a new band known as the Koola Lobitos, and quickly became a fixture on the London club scene.

Upon return to Nigeria in 1963, he formed a new version of Koola Lobitos, mixing influences from jazz, James Brown and traditional high life elements. In the first two years following his graduation from Trinity, his group released a couple of songs notably ‘Remi’, ‘To My Mother’, ‘Great Kids/Amaechi’s Blues’, amongst others. In 1964, Fela was hired by the Nigerian Broadcasting Company as a junior producer for Music Programming. He was fired from the position one year later.

Political awakening and the birth of Afrobeat

In 1967, Faisal Helwani helped to organize Koola Lobitos first media tour in Ghana. A second tour would follow the next year, following the release of the Fela’s first album, which was a compilation of the group’s songs. In 1969, Fela and his group embarked on a 10-month tour of America at the tail-end of the Civil Rights Movement, performing in different cities from a base in Los Angeles. In San Francisco, Fela met Sandra Isidore, a young lady on the fringes of the Black Panther movement, who helped introduce him to the works of Malcolm X and members of the Black Panther Party. He was deeply impressed and inspired by the ideologies of Black Nationalism and Afrocentrism embodied by Black Panthers and in ”The Autobiography of Malcolm X”, admitting that ”the whole concept of my life changed in a political direction.”

Building on this political revivification, Fela decided to leverage on his music to voice explicit criticism of political exploitation and intimidation of the oppressed and powerless. In a celebration to this new political education, he changed his group’s name to Nigeria 70. Following the opening of his popular nightclub, the Shrine, also known as African Spot in 1970, he again changed the group’s name to Africa 70 the next year. This period marked the birth of his signature Afrobeat, a dance musical genre with provocative political lyrics and traditional African rhythms, mixing call-and-response singing in pidgin English and Yoruba, with aggressive saxophone solos and African percussion and brass-section vamps, that suggest a rawer version of James Brown laced with African elements. Despite the hybridity of its origin, Afrobeat retained a unique originality and an African identity.

As Fela aptly puts it, ”I’m playing deep African music,”… I’ve studied my culture deeply and I’m very aware of my tradition. The rhythm, the sounds, the tonality, the chord sequences, the individual effect of each instrument and each section of the band – I’m talking about a whole continent in my music.” In the same year the group moves to a larger space, the Surulere Night Club, renamed Afro-spot. In 1971 Fela recorded his first political song- ‘Why Black Man Dey Suffer’ and the group made their first tour in Britain. Two years later, he released his first Afrobeat album, ‘Gentleman’.

Alagbon Close: the baptism of state aggression

On April 30, 1974, Fela was arrested by officers of the Nigerian Police Force, and detained for eight days at the Alagbon Close Police station in Ikoyi, Lagos. He was accused of hemp possession, drug addiction and abduction of under-aged girls.

In a desperate attempt to incriminate him, on May 9, 1974 just about 24hrs after his release from the Alagbon police cell, the officers returned to his house to plant a wrap of hemp and re-arrest him on that account. Fela was detained in a cell known as ‘Kalakuta Republic’ (Kalakuta = ‘Rascal’ in Swahili). This infamous cell inspired the song ‘Expensive Shit’ and he would even rename his communal residence-cum-recording/rehearsal studio, a two‐story building in the sprawling slum of Surulere, with the cell’s name, declaring it an independent republic immune to Nigerian law.

In response, on November 23, 1974, Fela’s residence, Kalakuta Republic, was again raided by the police. He sustained serious injuries from beatings by the officers, for which he was hospitalized for three days. ‘Kalakuta Show’ composed in 1976, was inspired by recollections of this brutal experience.

Carrying death in a pouch: the Kalakuta inferno

In 1975, Fela changed his last name from Ransome-Kuti to Anikulapo-Kuti, rejecting ‘Ransome’ as a slave name. (Anikulapo in Yoruba means ‘the one who carries death in his pouch’). In the same year, he also changed his band’s name to ‘Afrika 70’. The next year, he released a dozen angry songs scathingly attacking the government, denouncing corruption, multinational corporations, police brutality and ”V.I.P.-ism”. Some of the songs included the famous ‘Kalakuta Show’, ‘Yellow Fever’, Na Poi, Upside Down, Ikoyi Blindness, and the incendiary ‘Zombie’ which parodied the brutal mindlessness of Nigerian soldiers, who he described as do-as-you’re-told zombies who follow orders without any thoughts:

Tell them to go straight

A joro, jara, joro

No break, no job, no sense

A joro, jara, joro

Tell them to go killA joro, jara, joro

In February 1977 Fela completed the filming of his documentary movie ‘The Black President’. He declined participation in the 1977 lavish Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC), as a protest statement against the military government of General Olusegun Obasanjo.

Barely two days after completing the filming of his documentary movie, on February 18, 1977, acting under government orders, a mob of 1000 soldiers conducted a 15-hour vicious raid of Fela’s commune, in an apparent replay of ‘Zombie’. The occupants of the building and some innocent bystanders were physically assaulted and raped, and then arrested alongside Fela, who sustained multiple injuries.

About 60 innocent civilians were hospitalized following the tragic incident. Fela’s 82-year old mother, Mrs. Olufunmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was thrown off a second-floor window; she would later pass on from complications of injuries sustained during the attack.

The Kalakuta Republic compound, including his recording studio, master tapes and musical instruments, were razed down by the soldiers, while The Shrine was closed down by the government, effectively shutting down his group’s club performance, forcing them to move to Ghana on a temporary exile.

His album, ‘Sorrow, Tears and Blood’ released the same year was dedicated to the victims of the egregious Kalakuta attack.

A rosary of defiance and unrelenting political intimidation

In February 1978, Fela got married to 27 female members of his inner circle, a controversial move that stood in polar contrast to the feminist ideologies that his mother had championed. Shortly after, his band embarked on a tour in Ghana, during which Fela was arrested and detained for starting a political unrest. In September of the same year, after a performance in Berlin several of his band members including the talented drummer, Tony Allen, quit on account of his increasing political involvement. In the 1979 election, he declared his presidential aspiration, but his political party, Movement of The People, was banned from contesting. In the same year, he formed a new Afrika 70 band, and opened a new Shrine in Ikeja, Lagos, following the destruction of the original Shrine the previous year by soldiers.

On September 30, 1979, Fela and his supporters were beaten up by soldiers, after they marched to Dodan Barracks, Lagos to deposit a symbolic coffin for the Head of State, Gen. Olusegun Obasanjo, in honour of his mother and shame of those who he blamed for her death. He released ‘V.I.P-Vagabonds In Power’ and ‘Coffin For The Head of State’ in commemoration of this experience. In 1980, the government persuaded Decca Records to cut ties with Fela. The same year, he released ‘Authority Stealing’- one of his most controversial albums ever. In December 1981, Fela was charged as an accomplice in an armed robbery in Lagos. Although the charge was later dismissed, Fela nearly died from brutal beatings by the police before his release. He released ‘Original Sufferhead’ the same year. In 1982, Decca Records won a 120,000 Naira lawsuit against Fela and the government declared the Shrine as a danger zone, plunging Fela into near poverty.

In 1984, Fela was sentenced to five years imprisonment on charges of currency smuggling, initially jailed at the notorious Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison in Lagos and later transferred to Maiduguri Prison in northern Nigeria. His son, Femi, and his band (renamed Egypt 80 in 1981, as a statement of pan-African unity) continued performing at the Shrine. In October of the following year, he was named a Prisoner of Conscience by Amnesty International. Following a change of political administration and an unrelenting international effort to free Fela, he was eventually granted unconditional release in April 1986, after spending 20 months in prison.

The judge who declared the original five-year sentence later allegedly apologized to Fela. Following his release from prison in 1986, Fela released his famous ‘Beast of No Nation’, a caustic criticism of the Nigerian military regime, it’s tradition of human rights abuses and the circumstances surrounding his detention and prison experience, as well as the hypocrisy and complicity of world powers and global institutions like the United Nations in fostering systems of oppression and repression. Furthermore, after his release from prison, Fela announced his plans to revive his party, Movement of The People, and once again declaring his presidential aspiration.

In February 1987, a week-long event including a conference tagged ‘The Kalakuta Inferno and Human Rights in Nigeria’ was organized at the Jazz 38 Clubin to commemorate a decade since the infamous Kalakuta attack. Later in October of same year, Fela’s long-time friend, President Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso was assassinated in a military coup. His widely successful 1992 album, ‘Underground System’ was released in honour of his friendship with Sankara.

The later years: an unbroken spirit till the end

During a May 1988 conference by the Global Cooperation for a Better World in London, Fela was named Africa’s ambassador of cooperation and goodwill. In 1989, Fela and his band embarked on a three year tour across the US and Europe. During their US tour, Fela and Egypt 80 staged several important performances, including at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, in honour of James Brown who was unjustly serving a two-year sentence. Between 1993 and 1994, Fela performed mostly at the Shrine, where he was constantly harassed by the police, especially for his campaign for the right to smoke weed. During this time he was arrested and charged with complicity in the murder of a former employee of the Shrine; the allegations where later dismissed by a court.

In April 1997, Fela was again arrested and paraded on national television with over a hundred members of his residence by the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) on charges of illicit drug dealing. During the press conference, Fela vehemently continued to campaign for the right to smoke weed, declaring to reporters that “This grass is not harmful. It is medicinal. I have been taking it for 40 years and I can tell you that it is good. I know that cocaine and heroin are bad and I don’t take them and neither encourage people to take them”. Many however, believed that the government’s desperate attempt to habitually harass and arrest Fela on illicit drug dealing was merely a propaganda coating for a deeper vengeance for his anti-establishment songs and it’s ramifying influence among the Nigerian youths.

A statement released by Gani Fawenhinmi’s National Conscience Party in connection with the above arrest, argued that “Fela is being dehumanised by the NDLEA for using music as a means of mobilising public opinion against oppressive military dictators over the years. We, therefore, see Fela being chained as representing the radical movement and the masses of this country in chains of political and economic bondage.” The government further ordered a shutdown of the Shrine, although this was not effective as Fela and his band continued to stage performances there.

In June 1997, Fela cancelled a planned European tour due to an illness, later confirmed to be AIDS, which paradoxically, he had consistently denied its existence. Following unsatisfactory response to home treatment by his daughter, Omoyeni Kuti, he was admitted in a hospital in July. He later died on August 2, 1997 from complications of AIDS, aged 58 years, leaving behind seven children, over 50 albums and an enduring musical legacy which flame has blossomed on with his sons, Femi and Seun, and other descendants of the Afrobeat tradition. He was buried the following day at his Kalakuta Republic commune. His funeral drew more crowds of sympathizers than the procession for any previous Nigerian Head of State, with over a million people lining the road from Tafawa Balewa Square to The Shrine to pay their tributes.

A press statement issued by the United Democratic Front of Nigeria on the occasion of Fela’s death summarized the enduring substance of his life story: “Those who knew you well were insistent that you could never compromise with the evil you had fought all your life. Even though made weak by time and fate, you remained strong in will and never abandoned your goal of a free, democratic, socialist Africa.” As Michael E. Veal eloquently puts it, Fela’s “belief in transnational African unity, his fearless running critiques of corrupt and dictatorial regimes, and the political orientation of his popular art all contained critiques crucial to the survival of healthy African societies into the twenty-first century”.